Ceremony, culture, and the call to indigenise

Written by Leah Subijano | Published January 2026

Last November, I had the privilege of attending the World Indigenous Peoples’ Conference on Education (WIPCE) 2025 in Tāmaki Makaurau, Aotearoa. For the first time, it felt like all my worlds came together: culture, education, dance, ceremony, storytelling, prayer, healing, spirituality, decolonisation, and social justice.

The week was intense. It began with a powerful Pōwhiri and Parade of Nations, setting the tone for what was to come. Over the next four days, the program featured international keynotes, panels, academic and community presentations, and Te Ao Tirotiro cultural excursions. Alongside this was the vibrant Te Ao Pūtahi festival and daily social events. It was exhausting, yet every moment left me energised by the knowledge and mana shared by every speaker and every person I encountered.

What made WIPCE unique was its deeply intergenerational nature. Calling in ancestors into the space was the norm. Presentations opened with prayer and intention. Culture was front and centre, not something kept behind closed doors. People spoke truth to power, sharing wisdom rooted in lineages stretching back since time immemorial. It was a space where we felt valued, seen, and understood.

Ceremony, culture, and the call to indigenise

It was my first time experiencing a pōwhiri, a powerful ceremony led by mana whenua, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei. Thousands of us gathered, accompanied by the presence of our ancestors. My spiritual senses were in overdrive.

What followed was the Parade of Nations, an unapologetic explosion of colour, culture, and pride. Cultural attire shimmered in the sunlight, drums and chants reverberated against the city’s concrete walls, and dance infused rhythm into the heart of Auckland’s CBD. That vibrancy didn’t stop there; it pulsed through every fibre of the conference, embodying indigenisation in motion.

Science through story

This conference was a profound reminder of how colonisation disrupted our understanding of the deep interconnection of all things. Science is not divorced from song, dance, or story. And language is the thread that weaves together nature, culture, and knowledge.

“To write in our own language is to rewrite the world in our image. To teach literacy in Māori is to teach life itself, to remember that our words (worlds) are woven from the soil to the sea, the stars and beyond”

Indigenous knowledge systems encode scientific understanding through myths, legends, and oral traditions. These stories are vessels of learning from nature, preserving knowledge, and transmitting it across generations. Deep scientific knowledge lives in these narratives, whether in Hawaiian fishing techniques, Māori wayfinding practices, Neshnabek (Turtle Island) teachings on food chains, or Rukai (Taiwan) fire creation.

One example close to my heart is the understanding that Hawaiian hula is far more than entertainment. Mele (song) and oli (chant) are living repositories of ecological and cultural knowledge, teaching ways to live in harmony with the land. When missionaries arrived, deliberately destroying native culture, hula went underground. It became a powerful act of resistance, keeping the Hawaiian language and ancestral wisdom alive against active erasure. Today, this practice has transcended oceans and borders, inviting people across the globe to learn about Hawaiian culture, connecting Kānaka Maoli and non-Hawaiians alike through the depth, beauty, and knowledge embedded in hula.

Reviving ancestral intelligence

During the conference, I had the privilege of boarding the wa‘a Hōkūle‘a and her sister vessel, Hikianalia. These double-hulled canoes are not only central to Pacific identity, but they also represent a modern revival of ancient seafaring techniques. For generations, Pacific ancestors were expert navigators who crossed Moananuiākea (the Pacific Ocean) using traditional wayfinding methods based on the stars, ocean swells, bird flight, and other natural indicators. The Hōkūle‘a stands as a symbol of cultural resilience and Indigenous pride, carrying forward knowledge that was nearly lost. Both vessels had recently arrived in Aotearoa from Rarotonga as part of Moananuiākea, a four-year (2023-2027) circumnavigation of the Pacific. This 15th major voyage aims to preserve and perpetuate ancestral knowledge, strengthen cultural continuity, and advocate for ocean stewardship.

Nainoa Thompson’s presentation

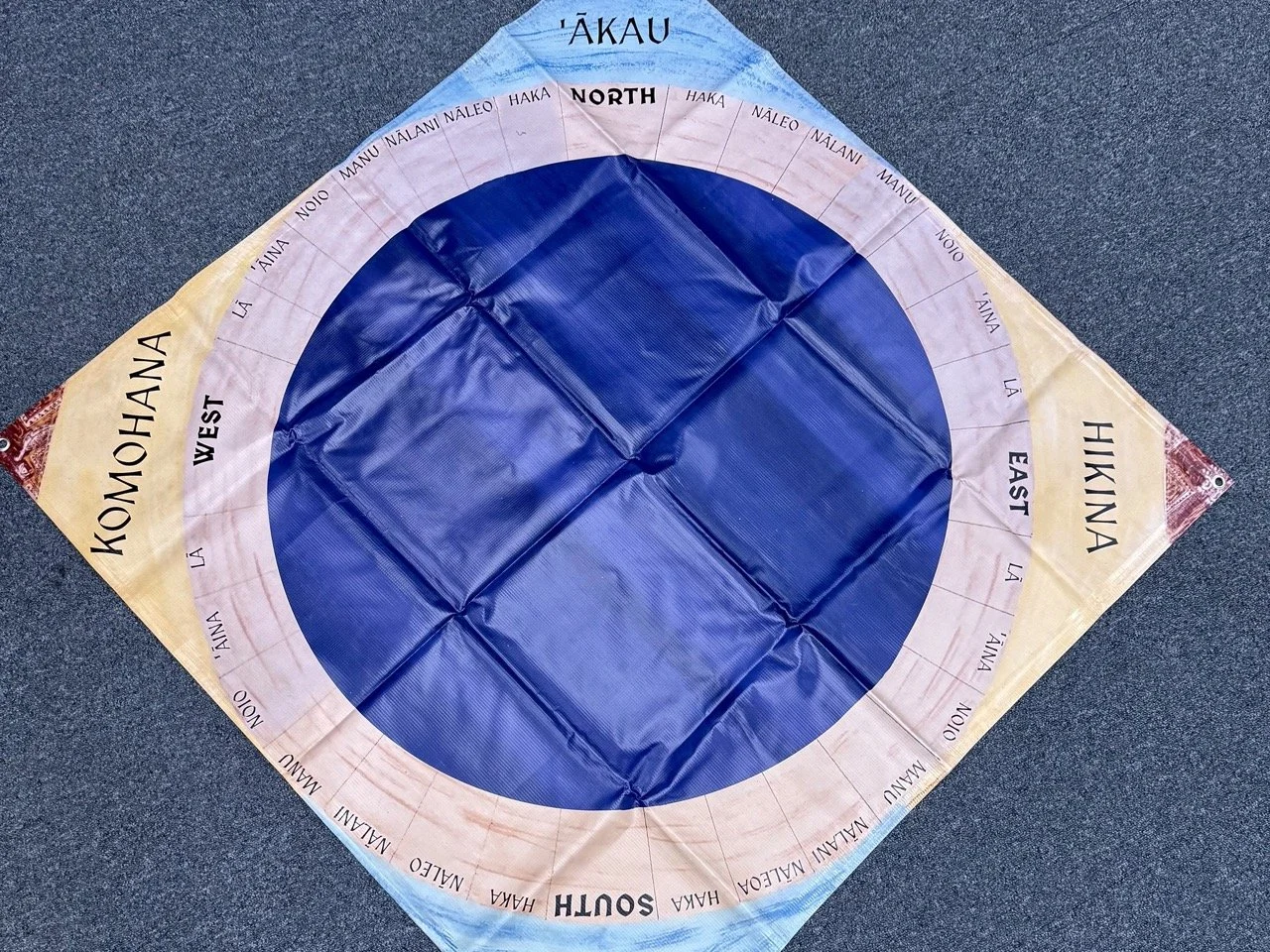

We learned about wayfinding through the Kūkuluokalani, the Hawaiian star compass, and explored how navigators read natural signs without modern instruments. The complexity and precision of these techniques are remarkable and underscore the depth of Indigenous science.

We also heard from Nainoa Thompson, a leading figure in the revitalisation of Polynesian navigation. His reflections spanned five decades of voyaging and the lessons learned from his mentors – his father, Master Navigator Mau Piailug of Micronesia, and his friend Eddie Aikau.

Mau, one of the last traditional navigators of his time, chose to share his knowledge with Nainoa in the 1970s to prevent its extinction. Eddie Aikau–a legendary lifeguard, surfer, and Hōkūle‘a crew member–tragically died at sea during the 1978 voyage after the vessel capsized. He attempted to swim to land to seek help but was never seen again. His sacrifice endures as a powerful reminder of courage and purpose.

“I don’t worry about you in a storm in the ocean. I trained you. Be humble to the storm in the ocean. Pay respect and pay attention. What I worry about is the storm inside you—your absence of courage, absence of faith.”

“Eddie is always with us… Eddie can help us find courage when we’re most afraid. He can help us know why we are here, what’s the destination, what’s your purpose.”

These words speak to the heart of voyaging (and life). Carrying on the legacy of teachers is not just about learning seafaring techniques; it’s about embodying values. Courage, faith, and resilience are the compass points that guide you when the path feels uncertain. Eddie’s story reminds us that even in moments of fear, the wisdom of those who came before can steady us and help us rediscover our purpose and direction.

Stepping aboard the Hōkūle‘a and Hikianalia reinforced the significance of cultural revival. These vessels represent more than seafaring; they embody the reclamation of knowledge, the restoration of dignity, and the continuity of Pacific traditions. They sail forward, rooted in Indigenous values, carrying the legacy of ancestors and reaffirming the interconnectedness of cultures across Moananuiākea.

Our responsibility as migrant settlers on stolen land

The Philippines, Hawai‘i, and Aboriginal Australia, like many other nations, share histories marked by violent colonisation and displacement, carried out at different times by different colonial powers. These legacies have shaped centuries of migration, creating vast diasporic communities. For many Filipinos, our parents and grandparents left the Philippines for countries like the United States, Canada, and Australia in search of better opportunities and security for their families. But beneath these stories of hope lies a confronting question: What is the cost of the freedoms we hold and living out our parents’ dreams?

One session that resonated deeply was Ancestral Echoes, Living Commitments: Honoring Indigenous Lands and Kanaka ‘Ōiwi as Filipino Settlers in Hawai‘i. Speakers Leslie Cabingabang, Rouel Velasco, and Mālia Michelle Ka‘io explored the tensions and solidarities between displaced peoples and Indigenous peoples of the lands we now inhabit. They spoke of learning to honour the places we call home while grappling with our own ancestral disconnections. Their message was clear: awareness must lead to action through a transformative process of learning and unlearning. This means shifting from diasporic ache to a responsible presence, moving beyond nostalgia toward truth-telling, and transforming the desire for belonging into a commitment to accountability.

Leah, Rouel and Leslie

Meeting fellow kababayan (countrymen) from across the globe was a reminder of the complex, entangled histories of settler colonialism - histories that not only displace Indigenous peoples but also reposition other colonised peoples into roles of both survivor and settler. As migrant settlers on stolen land, our responsibilities are profound. We must critically examine our positionality in the spaces we occupy, walk in solidarity with First Nations peoples, and act as stewards of the land under Indigenous leadership. This means advocating for Indigenous self-determination and sovereignty while ensuring that our actions reflect accountability and respect for the original custodians of this land.

For me, Australia has always been home. This land has fed me, its waters have nourished me, and its air has breathed life into me. Yet, it is not my ancestral home. This session was a powerful reminder that with this privilege comes responsibility–a responsibility shared by all non-Indigenous Australians. We must honour the sovereignty of First Nations peoples, challenge systems that perpetuate ongoing dispossession, and commit to walking alongside Indigenous communities in the fight for justice.

Decolonising in the diaspora through drum and dance

My poster presentation wove together many of these learnings and reflections. The journey to reconnect with my pre-colonial ancestral roots has been far from linear. It unfolded through creative practices such as ‘ori Tahiti (Tahitian dance) and Hawaiian hula with my dance school Nāpua Australia; and Afro-Brazilian drumming, with my women’s rhythm collective ILE ILU. Each of these art forms opens a doorway to a different way of being and knowing. These practices became conduits to Indigenous worldviews, calling me to connect more deeply with my roots and with spirit.

Immersing myself in these traditions revealed an entire universe of art, culture, and knowledge, while placing me at the threshold of another: the vast realm of pre-colonial Filipino myths, legends, and cosmologies. While I cherish learning from other cultures, there is an undeniable ancestral pull to turn inward and reclaim the rituals and stories encoded in my own bloodlines.

Cultural dance and drumming are not mere performances; they are repositories of knowledge, resilience, and identity, living archives that resist erasure and invite us to remember who we are. When we engage with these practices, even across cultures, they can become bridges of understanding and pathways to rediscovering our own ancestral traditions. Learning through other cultural frameworks often illuminates the stories, rituals, and wisdom within our own heritage, inspiring a deeper journey of reconnection.

And finally

WIPCE 2025 was more than a conference; it was a moment in time - a gathering of Indigenous Peoples from across the globe and a pivotal milestone in my own decolonisation journey.

I’m deeply grateful to all the incredible people I met along the way. And special shout-out to my fellow artistic brown island UTS sister, Christine Afoa, grounding me, sharing space to reflect, and making sure we had the most fun on this unforgettable adventure.

References

Inspiration for this article was drawn from the following WIPCE 2025 presentations:

Science and technology (keynote address) – Mere Skerrett

Connecting to science knowledge through Indigenous storytelling from around the world (breakout session) – Carley Malloy, Peresang Sukinarhimi, Julie Robinson, Waipapa Taumata Rau, Pauline Chinn, Piata Allen, Stacy Potes

Papakū Makawalu: Ancestral method of understanding our island environment (breakout session) – Kuulei Higashi-Kanahele

Wa’a Hōkūle’a & Hikianalia (Te Ao Tirotiro Excursion)

Ngāti Ruawāhia: 40 years of a shared Māori and Hawaiian voyaging heritage (breakout session) – Nainoa Thompson

Ancestral echoes, living commitments: Honoring Indigenous Lands and Kanaka ‘Ōiwi as Filipino Settlers in Hawai’i (keynote session) – Leslie Cabingabang, Rouel Velasco, Mālia Michelle Ka’io

Decolonising in the diaspora through drum and dance (poster presentation) – Leah Subijano

Return to Advocacy